Observations on the 28th UN Climate Change Conference – COP28, Dubai

28th UN Climate Change Conference – COP28 – Dubai, UAE (Nov 30 – Dec 13 2023

DECSY Global Education Adviser, Rob Unwin, attended COP 28 as an online observer. He writes:

My overall impressions were of a sumptuous venue with ambient oud music, stars and sand dunes and then blue whales and sea turtles swimming 360 degrees around us, powerful speeches about the need to act and side rooms full of mostly young delegates diplomatically thrashing out the details. With nearly 200 countries represented and around 85,000 participants, including 2,400 people connected to the coal, oil and gas industries, and the event presided over by the CEO of his country’s state-owned oil and gas company, it felt that significant progress was unlikely. However, as the UN Climate Change Exec. Sec reminded us ‘Without [these conferences] we would be headed for close to 5 degrees of warming. An open-and-shut death sentence for our species.’ The Energy Institute even suggested that the dual role of the COP president, ‘may have been intrinsic to reaching the final outcome’ of an agreement for the need to transition away from all fossil fuels (far below what many sought, yet a first in the three-decade history of COPs).

around us, powerful speeches about the need to act and side rooms full of mostly young delegates diplomatically thrashing out the details. With nearly 200 countries represented and around 85,000 participants, including 2,400 people connected to the coal, oil and gas industries, and the event presided over by the CEO of his country’s state-owned oil and gas company, it felt that significant progress was unlikely. However, as the UN Climate Change Exec. Sec reminded us ‘Without [these conferences] we would be headed for close to 5 degrees of warming. An open-and-shut death sentence for our species.’ The Energy Institute even suggested that the dual role of the COP president, ‘may have been intrinsic to reaching the final outcome’ of an agreement for the need to transition away from all fossil fuels (far below what many sought, yet a first in the three-decade history of COPs).

Having only caught glimpses of the inner ‘Blue zone’ at COP 26 in Glasgow, I was fascinated to see the national interests of the different participating countries exposed in real time and to appreciate the enormously complicated task of hammering out agreements. I saw a young Saudi woman embellish their carbon capture technologies, a Russian woman promoting natural gas as the transition fuel we need, and a Kazakh delegate championing the country’s uranium. The UK team seemed in a weak position, promoting fossil fuel phase down so soon after their government had decided to issue new North Sea oil and gas licenses.

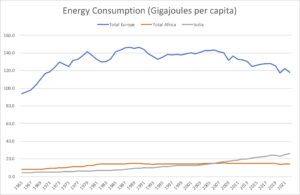

An overriding theme was ‘developing’ countries arguing that ‘developed’ nations must compensate for their historical emissions before the rest of the world makes sacrifices. This is not just about early industrialising countries disproportionally contributing towards climate change and many less industrialised nations disproportionately suffering the ill effects; the crux of the matter seems to be the energy inequality between the ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’. The current energy gap between Europe and Africa (and India) for example is extreme.

An overriding theme was ‘developing’ countries arguing that ‘developed’ nations must compensate for their historical emissions before the rest of the world makes sacrifices. This is not just about early industrialising countries disproportionally contributing towards climate change and many less industrialised nations disproportionately suffering the ill effects; the crux of the matter seems to be the energy inequality between the ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’. The current energy gap between Europe and Africa (and India) for example is extreme.

In ‘Material World’, Ed Conway writes, ‘In energy per capita terms, many nations remain where Britain was in 1800.’ This isn’t just about powering homes but is mirrored by the amount of energy-intensive steel per person (around 11 tonnes per person in Europe and around 1 in Africa) and many other materials used in infrastructure (hospitals, schools, work places, transport etc) that contribute to a standard of living taken for granted in the ‘Global North’. Countries that have built their economies on their oil, gas or coal production are also going to be reluctant to take the hit. So, pushing for the phasing out of fossil fuels to give the massive emissions cuts required to limit global temperature rises to 1.5 degrees, the target agreed at Paris, is going to need a surge of finance.

Encouragingly, agreements were reached to double the average annual rate of energy efficiency improvements, to triple renewables (though not signed by China or India) and to cut methane emissions by at least 30% by 2030. However, I saw instances of ‘Global North’ country teams trying to down-play agreed principles of cooperation, equity and ‘common but differentiated responsibility and respective capacity’ to avoid taking the lead in energy transition or providing adequate finance to support others to do so. As a consequence of this pattern of behaviour at previous COPs, many countries of the ‘Global South’ explicitly made the implementation of their ‘Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)’ (towards the 1.5 degree goal) conditional upon international support in the form of financing, technology transfers and/or capacity building. This weakens the whole process of meaningful climate change agreements and strengthens the case for ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ countries being required to provide detailed, verifiable, information regarding international support received and delivered as part of their NDCs. It may be something that new carbon trading mechanisms (due to begin in 2024) also seek to address.

Perhaps the criticism of the COP president’s oil links held his feet to the fire and a long-awaited agreement to set up a ‘Loss and Damage Fund’ was made on the first day of the conference. This had been campaigned for by 134 countries of the Global South, including the small island nations, to help pay for the huge damages already suffered due to climate change. The finance pledged so far (controversially to be initially hosted by the World Bank) is perhaps four hundred times below what’s required, but it is a significant first step.

Other agreements made at COP 28 included support for ‘regenerative agriculture and resilient food systems’. Critics have questioned whether this may benefit big companies more than small-scale and indigenous farmers and advocate more localised solutions that have already proven effective, such as agroecology. An agreement on climate measures relating to health was also made, though not about waiving intellectual property rules to facilitate technology transfer. Brazil, which will host COP 30, announced a ‘Tropical Forests Forever’ fund linked to carbon offsets and countries pledged to link future NDCs to their national nature plans. Inclusion and human rights had gains and losses, with some recognition of gender, Indigenous People, children and youth, and people with disabilities, across different strands of the negotiations, but with only one weak reference to human rights in the core text.

It seems apparent that this ‘Only game in town’ for addressing climate change internationally needs true leadership, backed up by action and serious finance by those nations with the means. That in turn requires their civil societies to support such sacrifices and action for the sake of us all.

Credits:

Photograph: Isabel Prestes da Fonseca UNclimatechange CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Deed.

Graph: Data source: The Energy Institute.

This article was originally written for, and is reproduced with kind permission of SCI (https://sci.ngo)